Welcome to Life after Trauma. Today, I’m answering one of the most common questions I get: how did you survive what happened to you? Usually the ‘Ask Clare’ column is for paid subscribers only, but I’m making this edition available for everyone. If you value having a survivor’s perspective on these questions, please consider paying me for my work. Your support directly impacts the depth, scale and sustainability of my ability to support survivors in some of the most painful moments of their lives.

We’re starting the Artist’s Way next week!

Creativity was a big part of what helped me heal after sexual trauma (read on to see just how much it helped!), and I’m excited to explore this theme over the next few months. Here are all the details, but to summarise: we’ll be reading a chapter each week and gathering to share our experiences in the comments on Friday. Many people find The Artist’s Way to be overwhelming, so I’m proactively scheduling in some rest weeks and encouraging us to show up consistently but imperfectly. There are no prizes for completion, but there’s lots of encouragement for giving it a shot. I can’t wait to get started next week!

I recently posted a Note about my work volunteering with the Rape Crisis Centre. My role involves accompanying people to the Sexual Assault Treatment Unit and supporting callers to the national helpline. It isn’t always easy, but it’s among the most meaningful work I’ve ever done. “Sacred” was the word a commenter used to describe it, which feels right to me.

For the most part, my role is to sit with people who’ve been assaulted and allow them to be. Sometimes, they prefer to sit in silence. Other times, they have questions. Almost always, there’s one big question hanging in the air: how the hell am I gonna survive this?

There’s no single answer to that question. Every person who’s experienced sexual trauma has to find their own way through it. Not everyone survives. Some are murdered by the perpetrator in the immediate aftermath of their assault. Others don’t survive the scale of the violence inflicted on their bodies.

Sometimes survivors reach out to me directly, and ask: how did you survive? But more often, the question hangs in the air. I can see desperation in their eyes, and their grasping panic for somewhere solid to stand as their world implodes.

I’m going to try to answer that question today. But first an enormous caveat:

There’s no internet ten step list that can help heal the devastation of sexual trauma. There’s nothing you can read here that will change what’s happened to you, or even make it easier to live alongside. The harm we’ve been subjected to will be with us for the rest of our lives and I recoil at anything that purports to be a quick fix, or a cure all.

Everyone’s path is different, depending on their own unique circumstances and experiences. You are the best person to know what would help you heal, and I hope you’ll trust that inner knowing more than my POV.

As I wrote this essay, I was struck by how tidy it feels. As if there’s some recipe for healing that can be copied and pasted. Recovery isn’t like that. If you’re crying 16 hours a day, please know I did that too. In the immediate aftermath of an assault or when processing memories of a past trauma, just existing from day to day is enough. Just existing day to day is a lot.

Please don’t read this list and feel like you should be doing more. Surviving is enough. Existing from day to day is enough. If you have some capacity and want to try something, I hope this essay will be a useful starting point. But if you want to close the screen and nap instead, please do.

When I was in the depths of my trauma, I would have given my right leg to know that what I’d been through was survivable, that life could be worth living again. This was long before #MeToo, long before there was any public conversation of the impact of trauma on people’s lives. Like many survivors, I struggled to get adequate support and found myself googling desperately trying to find a way forward. This is the list I wish I’d found back then.

With the possible exception of writing, nothing that’s included below worked for me 100% of the time. For long stretches, all I could do was cry and try to numb out. I watched a lot of TV, listened to a lot of podcasts and spent a lot of time in bed. I could (& maybe one day will) write a book on this topic, but for today, I’ll try to be brief. I hope you’ll also add your suggestions and ideas in the comments.

I’ve a lot to say on this topic, so it’ll probably get cut off in your inbox. Click through to read the full essay here.

Here are some of the things I did to recover from sexual violence:

I quit my job

I hit rock bottom in 2018. I’d just resigned from my job with Amnesty1, and was deeply traumatised by the work I’d be doing there. I couldn’t sleep. I couldn’t eat. I couldn’t exercise. I couldn’t concentrate. Looking back, this was a turning point in my life. It was the moment I decided to take all the energy and ambition I’d been devoting to my career, and invest it in my recovery instead.

I know this isn’t possible for everyone. I was terrified to leave my job, and knew I was putting myself at risk financially. But my role was untenable and looking back, I’m honestly not sure I’d still be here if I hadn’t found the courage to resign.

When I was ready to return to work, I left the nonprofit world behind and got a boring job that I was way over-qualified for. For the first time in my life, I had a job I didn’t care about. I quickly learned how good life can be when your identity and self-conception exist apart from your working life. When I was working traumatic jobs, my recovery always felt so fragile. I was travelling to difficult environments (Gaza, refugee camps) and living under the whims of bad bosses. It broke my heart to leave behind the career I’d worked so hard to build, but it was also the start of a new, healthier chapter.

A safe, secure home

At the time, I was renting a small, mouldy flat but I made it feel like home. I lined the walls with books, and invested in cozy bed sheets and towels. I wasn’t earning much, so I lived cheaply on eggs and beans. I went to the library. I took long walks in nature. I rested. From the outside, my life looked really dull but for the first time in a long time, it felt stable to me. Creating a safe, secure home for myself was key to my recovery. It took me many years to achieve that goal, but it was deeply worthwhile.

Therapy

When you disclose that you’ve experienced sexual violence, people always suggest therapy. To me, the tone often sounds like this:

“Wow, you must be so fucked up now. You should really go to therapy. You are damaged goods, and we can’t have you walking around in the rest of society, with us good, non-damaged people”.

It’s possible that I’m projecting, but it’s also possible that people are so terrified by sexual violence that they immeadiately want to call the professionals to contain it. As if survivors are some sort of contaminant, unfit for interaction with the rest of the world. I have a lot of therapy baggage. I’ve written about some of my experiences here. I had to “audition” a bunch of therapists before I found someone I felt I could work with and even then, the process was brutally difficult. I would often leave therapy and cry for days. There were times that trying to get well was making me so much sicker. But I stuck with it and I’m glad I did2.

Going to therapy wasn’t the only or even the most important thing I did for my recovery. It was one piece of the puzzle, not the whole thing. In my experience, a little skepticism of therapy and all its flaws and promises is a useful thing.

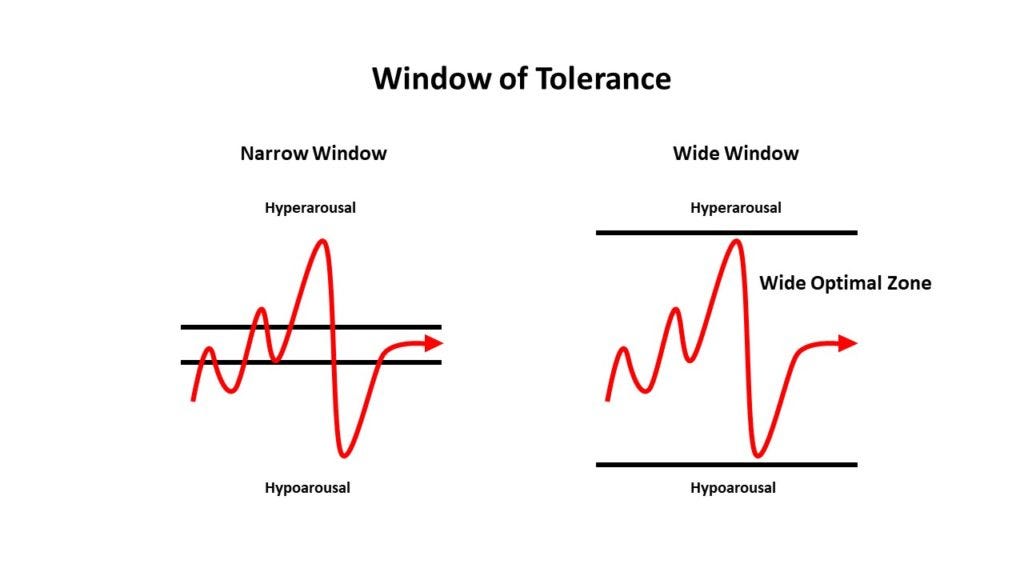

Understand your window of tolerance

One of the most useful concepts I learned in therapy was the Window of Tolerance. Developed by Dan Siegel, the Window of Tolerance is the optimum zone in which we function well. In this zone, we can cope with the normal ups and downs of life without too much difficulty.

Grief, trauma or other adverse experiences cause our window of tolerance to narrow. Things that we would have been able to manage under normal circumstances suddenly become overwhelming and distressing. We can also widen our window of tolerance by taking good care of ourselves. Things like rest, gentle exercise and creative practices allow us to rebuild our resilience and widen our window of tolerance.

That’s not always easy to do, but having the language to understand how I’m managing my life and my C-PTSD symptoms has been very useful to me. Here’s a free resource (PDF) about the window of tolerance if you’d like to learn more.

Numbing (in a healthy-ish way)

Sexual violence overwhelms us. Our bodies and minds become completely overloaded by the violence we’ve experienced, and it can be severely debilitating for the body. For a long time, I was so physically, mentally and emotionally exhausted by what I’d been through that I struggled to cope with life. I had to numb my thinking mind, and give my body a chance to process everything I’d been through.

For me, that looked like watching truly Olympic levels of television. If my mind was free to wander, I’d have flashbacks and nightmares. To stave off that horror, I pumped stories into my brain. I listened to dozens of podcasts, and kept myself company with the voices of strangers. I’d come home from work and climb straight into bed. I spent hours there - crying and raging and trying to numb myself. Sometimes that helped. Often, it didn’t. In those moments, I learned I needed a plan.

Have a plan for when you get triggered

For many of us, there’s very little we can do to avoid being triggered. For a long time, the circumstances of my life were so painful and it was impossible to avoid that agony. But over time, I got better at taking care of myself through the triggers.

For me, the best place to be was at home in bed with my laptop for company and light, bland food to sustain me. I cried a lot. I read a lot. And I tried to get out for walks.

The specifics of what you do when you’re triggered are less important than having a plan. In a more steady moment, think through what you’d like to do the next time you get triggered: where will you go? What will you do? How will you support yourself through it?

In the last few years, I’ve come to think about triggers like tummy bugs. They are vicious. They rage through your body, destroying all normalcy and inflicting untold anguish. But they pass. The worst of it is usually gone within 48 hours. And my job is to be as kind as I can to myself through those difficult days.

Honour your feelings, especially your rage

It often seems like our society is in denial about the true prevalence of sexual violence. Repeated surveys have found that it is heartbreakingly common, yet there’s almost no dedicated state or societal response. #MeToo went viral in 2017, but what systemic change has resulted from that mass movement of self-identification by survivors on social media? Very little3.

When I was drowning in trauma and the world was happily trundling along as normal, I felt like an alien who’d arrived from another planet. The therapists call this ‘derealization’ and it’s a horrible thing to feel. When everyone around you goes along with the kind of normalised sexual harm I was experiencing on a daily basis, you start to feel crazy. But you're not crazy. The culture needs to change, not you.

One of the things that got me through was staying connected to my fury that anyone would have to survive this trauma alone. Most survivors have moments of devastating sadness, hopelessness and despair but in my experience, it’s harder for us to feel our rage. For me, anger has been a kind of fuel, a propellant that has kept me going. It drove me to start Life after Trauma, to volunteer with other survivors and to imagine what a different world might look like. I owe my rage a lot.

Step back from relationships that hurt you

Perhaps the most difficult thing I did as part of my recovery was to take a step back from important relationships. For a few years, I was so triggered by certain people that I’d cry for days after interacting with them. The reasons why are complicated. Most of the people I stepped back from during this time are good people, who undoubtedly have their own perspective on how I was behaving. They probably thought I was being oversensitive/moody/demanding/angry.

It broke my heart to withdraw from the people I loved, the people who brought fun and pleasure and interest to my life, but it was also necessary. It allowed me to break out of a cycle of being continually hurt and gave me the space to heal and build a better life for myself.

Part of healing is establishing better boundaries. I learned that not everyone has earned the right to hear my story. I learned to protect my vulnerability, which sometimes means stepping back from certain relationships. Isolation isn’t always a bad thing. Sometimes it’s what you need to heal. The typical advice in a crisis is to ask for help. We’re warned not to isolate ourselves. I tried that (wow, did I try) but ultimately, it didn’t help.

Sexual violence is among the heaviest aspects of human experience. It’s not something everyone has the strength to hear about. I try not to blame people for that. If I hadn’t had my own experience, I don't know if I would’ve been able to be present for other survivors. I try to see the good in people, which is only possible because I also have strong boundaries.

Learn to trust myself and my instincts again

My most painful relationship through this period was the one I had with myself. I didn’t think I deserved to live. I didn’t think I was worth saving. I thought I’d made such a mess of my life, and kept making it worse by choosing bad relationships and a career that brought me into contact with some of the darkest aspects of humanity.

An example: When I worked in UNICEF, I got an email from HQ every morning which listed all of the horrible things that had happened to children in the previous 24 hours. It was my job to choose4 which of those issues to work on, and which would be left aside. I organised press trips, bringing journalists to see our programmes in refugee camps in Jordan and Lebanon, and in Gaza. Each trip took a toll on me, but I couldn’t leave the job. Money was part of it - I was broke, and needed to work. But I also couldn’t disentangle myself from the trauma of it.

Looking back, I can see how witnessing that kind of destitution warped my mind. I can see how my traumas cascaded and intersected, exacerbating each other and tightening their vice grip around my throat. During this time, I saw a lot of myself in stories of people struggling to leave abusive relationships. I was in a toxic relationship with my work, and I couldn’t find a way out.

It took me a long time to forgive myself for those choices, and to rebuild trust in myself again. Therapy helped. So did making & keeping small promises to myself. So did learning more about how trauma had warped my understanding of the world.

I read about trauma and recovery

When my parents’ marriage began to falter, I remember reading a Judy Blume book about divorce. It was the start of a life-long habit of reading about the things I’m going through.

While I was in the depths of my trauma, I read about how the brain and body responds to trauma. I read about recovery, and what it could look like. I read feminist texts about sexual violence as a tool of torture and oppression. I read to understand what was happening to me, and to find my way through. I’ve been building a resource library with some of the best things I read during this time: here are some great books and articles to get you started.

Rest

Of all the things I did to recover, this was maybe the most difficult. Growing up, I never really saw anyone rest as a proactive aspect of self-care. I’d seen people collapse with exhaustion at the end of the day, or have to manage the illness that came with overdoing it. But I never learned the importance of rest as an activity in itself. In a lot of ways, that’s what my body needed the most. I needed time to heal. I needed more rest than I felt I needed or deserved. I needed cozy blankets, comfortable clothes, hot tea and plenty of sensory comfort. In difficult moments, I tried to make sure I was as physically comfortable as possible. I rarely felt like I deserved to be comfortable, but I did it anyway and it helped.

Learning to move my body again

As I recently talked about on the podcast, most kinds of exercise were too triggering for me during the worst of my trauma. After going to the gym, I’d be so agitated that I couldn’t sleep properly for days. I read that how yoga could be helpful for people who’ve experienced sexual violence, but when I lay down on my mat, I would instantly start crying and shaking and feeling like I might vomit.

It took a long time, but consistent small steps (& a lot of self-compassion) made it possible for me to do yoga again. Some practical things that helped were keeping my eyes open and using my hands to ‘ground’ the parts of my body that felt unstable (for me, it was often my hips). When I felt able to, I tried to breathe through my triggers. I tried to relax into feeling embodied, and consciously rebuild the connection between my body, mind and breath. It was incredibly difficult. Really, I’m struggling to convey how painful it was. But over time, it did get easier.

These days, I roll out my yoga mat most days of the week. On the days it feels like too much, I get out in nature instead. I take long walks, inhale the fresh air and see some cute and happy dogs. I always feel a little better after.

Writing and creativity

The most important thing I did during these years was write. I wrote everyday, often for hours. When I got hurt or triggered or panicky, I wrote. I wrote when I felt better, making plans and lists for how I could turn things around. I used fiction to process things. I wrote a novel loosely based on my own life, and winced when I realised that I’d put my fictional protagonist through too much suffering though it was only a fraction of what I’d experienced. After a horrible breakup, I rewrote the experience as fiction, and reclaimed some agency by emotionally devastating the fictional character who was really a thinly disguised version of myself.

Writing was what saved me. It’s what made it possible for me to keep going. When I reached the limits of what language could convey, I experimented with art therapy. I made collages which allowed me to layer different & often conflicting feelings and ideas. I drew things I could express through language, and filled dozens of journals with all the things I needed to say but I couldn’t.

I had a dream

I had a reason to keep living. That reason was writing. I dreamed of being a writer. I dreamed of getting through my trauma, and being able to help other people. That dream kept me alive. I’m crying, as I write this because I’m not sure I would have made it without it.

I was too traumatised to imagine having a partner or getting married or having a more “normal life”. But writing always felt like an achievable goal. I knew I was a good writer, and that I would work hard to get better. I dreamed that it might be the thing that changed my life. In the end, I was right.

Writing didn’t save me in the way I thought it would. I thought I’d publish books and be “successful” in all the usual ways (bidding wars, bestsellers etc). In the end, writing saved me in a much quieter way. It kept me company when I thought I might die of loneliness, and allowed me to work through everything I’d been through. It kept me alive long enough for my life to change.

Curious about exploring your own relationship to creativity? We’re about to start The Artist’s Way and you’re so welcome to join us:

(gently) push myself beyond my limits.

During the most painful years, trauma shrunk my life down to the size of a postage stamp. I’d wake up early to write, go to work and be in the office for 10+ hours before going home to eat dinner and numb out watching TV in bed. I spent all my weekends at home, reading and writing and bracing myself for the week ahead.

I had no real connection with people. I had no real friends or social life. I’d say hello to the bus driver or the checkout worker or a colleague at work, but years passed without me having a genuine conversation with anyone. I was so on edge that I couldn’t bear to sit in a coffee shop and enjoy a pastry. Everything was a trigger, and it made my world smaller and smaller.

I reached a point when my life became so small that I was determined not to let trauma shrink it anymore. I pushed myself to slowly regain some of the ground I’d lost. I started going to a meditation class. I’d sit in silence with strangers for an hour, maybe join them for a coffee and then come home and lie on my bed. It completely exhausted me. But I kept going and slowly it got easier.

Volunteering

I started volunteering at a children’s hospital. On Friday nights, I’d take the bus to the hospital and sit with the babies who were too sick to go home. I gave their parents a chance to take a break for a shower or a bite to eat, while I sat with their children. It meant that for a few hours each week, I focused on helping someone else. Sitting with the babies, I didn’t have to do much. For the most part, they just didn’t want to be alone in their pain. I could sit with them and comfort them, and for a few hours, feel like I was doing something really worthwhile.

Find some people to look towards

One of the hardest things about that time was how alone I felt. Part of my trauma originated from my work with charities. I was working in the organisations that are supposed to help people, and I had direct experience of just how poorly they treated their staff. Knowing the extent to which “the helpers” were part of the problem really exacerbated my pain, and made it so much harder to believe that people could ever be good.

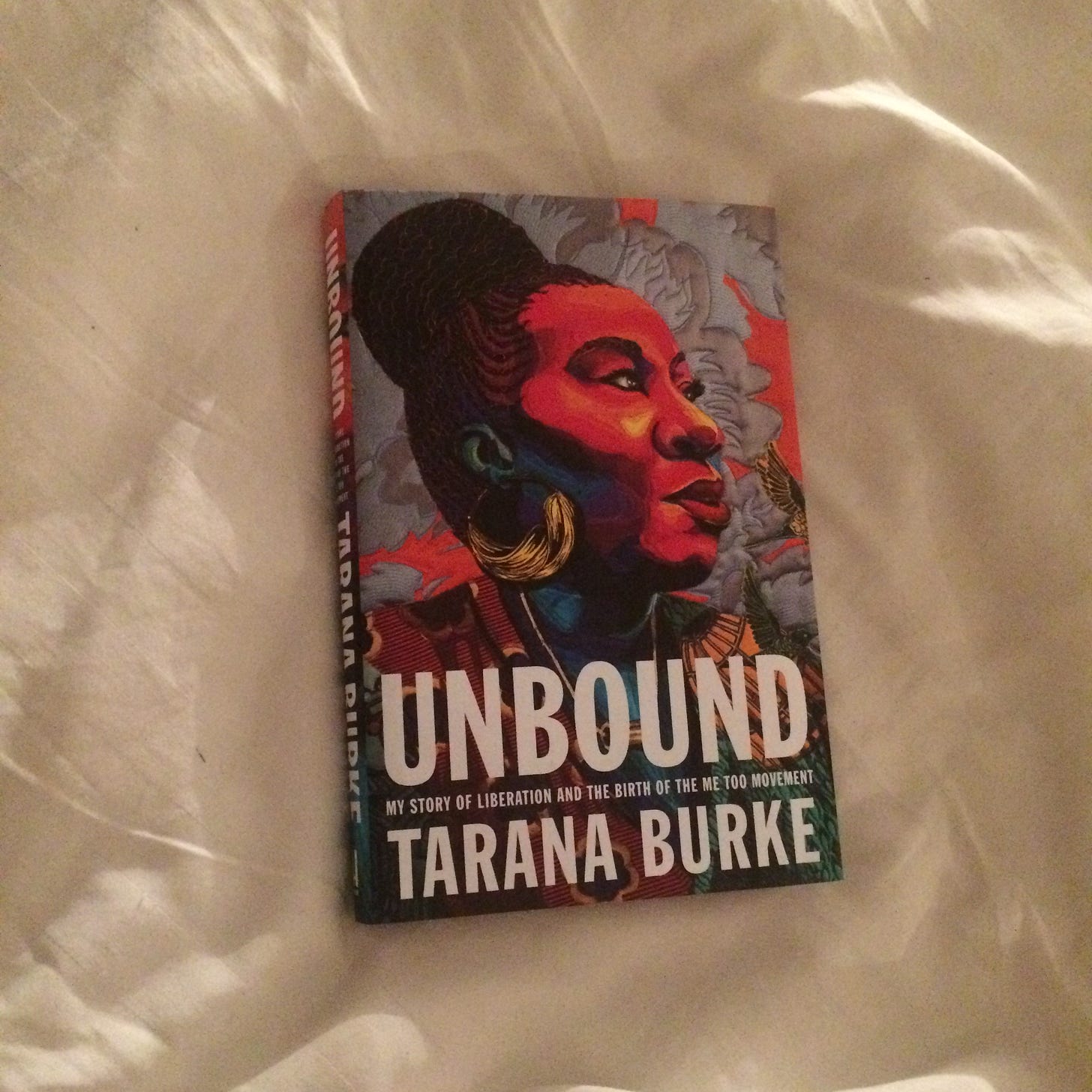

I needed to find some good people to look toward. People who could help me see that it was worth staying alive in this broken world. Tarana Burke was one of those people. I watched every video of her published on YouTube5 and found sustenance in her relentless focus on survivors and their recovery. I consumed hundreds of books, articles, podcasts and films featuring other survivors' stories. You might expect those things to have been triggering, and sometimes they were. But more often, I found solace in knowing that I wasn’t an alien who’d landed from outer space but part of a silent army of survivors suffering in isolation.

Time

I’m hesitant to include this. After my mother died, lots of people told me that time would help me heal. It was an incredibly frustrating thing to hear, but I also think it was true. I’ve felt her loss differently as I grew up. The same is true for my recovery from childhood sexual violence. I aged out of being seen as a sexual being. As the decades passed, I sorted through that trauma and built a new life on more solid foundations. I bought a home. I established a professional identity. I came out.

Around me, the culture has changed too. It’s a very different thing to write about sexual violence in 2025, than it was in 2005 or even 2015. The cultural change hasn’t gone nearly far enough, but there’s a lot more space for the kinds of stories I want to share than there was before. I’m grateful for that, especially to the people working on the frontlines of this issue.

When you’ve been suffocated by trauma for more than a decade, it doesn’t feel like your life will ever change. But it does. Time passes. The culture changes. People die. And, new chapters begin. You just have to stick around long enough to see it.

(I wrote about this concept in more detail here)

💕 If this piece resonated with you, please tap the heart below to help spread the word.

💬 In the comments, I’d love to hear about the things that have helped you through trauma. There’s no straightforward path, and I’m curious to know what your recovery looks like. Your suggestion might make a difference in another survivor’s life, so please don’t be shy.

At the time, I didn’t know just how toxic the organisation was. But within a few months, two former colleagues had died by suicide. One man left a note explicitly citing mistreatment at work. Last year, a man I worked with in Amnesty was sentenced for sexually assaulting a woman on his team at a work social event.

I've found 'inner child work' to be particularly helpful. It's a bit cringy but, in my experience, it also works.

To be clear, this is a critique of our society not Tarana Burke's ground-breaking movement for change.

These decisions were made in conversation with colleagues, though that did little to lessen the weight of them.

Of the dozens of clips I watched, this was my favourite.

I also took time off work, and ended up moving back in with my dad. It has been immensely difficult in many ways but I really needed to use the precious energy I had left and focus on healing.

I also left an emotionally intense job working with kids, because I was just always on high alert, worrying about everything I did/didn’t do, constantly listening out for signs of abuse etc. I took a really mundane admin job which bores me to tears, but has freed up a massive amount of headspace and rarely stresses me out.

Therapy, in particular somatic work, Internal Family Systems, and EMDR, have been transformative for me, as they have really helped me piece together what’s going on and tackle things before they get worse.

Love these actionable suggestions, and that there are enough to mix and match.