Survivors on Screen #1: Promising Young Woman

What the film’s critical response says about cultural attitudes to rape

This is the first installment in a new series about how sexual violence is portrayed in TV and film. Please be aware that some readers might find it triggering and that there are spoilers ahead. Here’s the introductory post, if you’d like to read.

Promising Young Woman stars Carey Mulligan as Cassie, the best friend of Nina who was raped at a college party and later died by suicide. In a haze of grief and guilt, Cassie wants to avenge Nina’s assault. It also stars Bo Burnham as Ryan, Cassie’s boyish love interest, Alison Brie as a former college classmate and Connie Britton as the college administrator who failed to punish the rapist.

It’s a bold and provocative film; part-black comedy, part-crime drama and part-vigilante thriller. Emerald Fennell (who previously worked on ‘Killing Eve’) wrote, directed and co-produced the film and also won the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay. It was released in 2020 and grossed $19 million worldwide. According to Rotten Tomatoes, audiences also enjoyed it.

With some notable exceptions, the reviews I read were full of dangerous falsehoods about the impact of sexual violence, what we expect of survivors and their loved ones and how we subtly (or sometimes not so subtly) judge how they behave in the aftermath of violence. They asked reductive questions about what’s considered an “appropriate” response to rape and the role of justice in a world where too many people (of all genders) experience the trauma of sexual violence. I read half a dozen reviews and was left with the sense that critics just didn’t get it. They didn’t see how their reactions fed into the tropes this film was trying to upend. They didn't see how their Himpathy, which philosopher Kate Manne defines as the cultural tendency to value men’s feelings over the feelings of the people they’ve hurt, was obscuring their critical faculties. It’s perhaps unfair to expect film critics to be trauma experts. Their job is to make judgments about the artistic quality of the film. But in doing so, they also betray their & in many cases, society’s ignorance and biases.

Visual identity

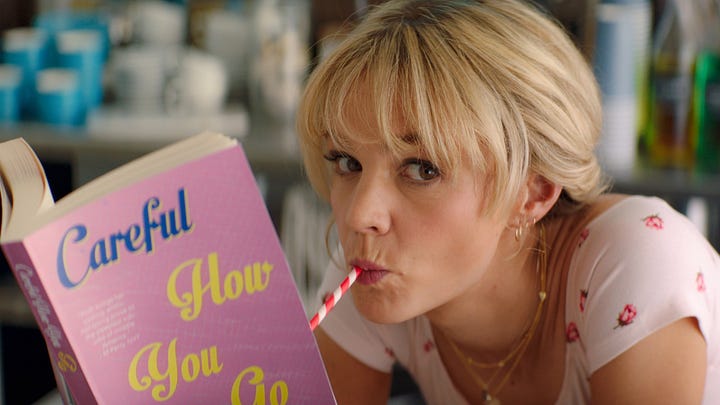

Promising Young Woman was the pinkest film I’d ever seen (pre-Barbie) and leans into a hyper-feminine aesthetic. During the day, the palate is pastel-hued. Cassie works in a coffee shop where she’s styled like a Shepherdess1 with a rainbow manicure and endless wavy blonde hair. At one point, she is framed so it appears she’s wearing a halo!

At night, the palate turns lurid. Angie Wells, who led the film’s makeup department, spoke about the importance of imperfection in how she looks. Watching a makeup tutorial for “blowjob lips” online, Cassie applies the lipstick perfectly and then smears it in a visual nod to ‘The Joker’.

Her self-presentation is, of course, strategic. Rather than shying away from her femininity, Cassie weaponises it. The film captures how women use their appearance to hide whatever is roiling underneath. In the world of the film, girlishness and darkness coexist, intermingling and warping each other. The film doesn’t acknowledge it, but Cassie’s whiteness makes this possible. Her white, blond femininity makes her appear vulnerable and innocent, in a way that women of other races rarely do.

Hunting

The early scenes of the movie follow Cassie as she hunts. From the trailer: "Every week, I go to a club. I act like I'm too drunk to stand and every week, a nice guy comes over to see if I'm OK." She goes home with these guys, seemingly incapacitated only to reveal her sobriety in the moments before they assault her. Fennell has spoken about the care she took in shooting these scenes. She cast male characters who audiences know and directed them to act as if they were the romantic lead:

“[Cassie] doesn’t entrap anyone. She never says yes, she never says no. She just exists. She says, ‘I’ve lost my phone,’ and then they do all the talking.” What you see, Fennell said, “is a man thinking he’s got a rapport with a woman, which I think happens a lot. It’s just that he hasn’t noticed that she’s not said a word.”

We watch these men edge toward violence, and see the moment they are confronted with their behaviour. She forces men, who consider themselves to be “good guys” but come perilously close to violating her, to confront their own worst selves.

I loved those scenes. The tonal shift from ‘good samaritan’ to ‘budding predator’ felt viscerally familiar to me. Some of the satisfaction, I’m sure, is the subversion of the story I’ve absorbed since childhood. The idea that if a woman is drunk, she is “asking for it”. Cassie weaponises that idea and inverts the common story. “I’m a nice guy’” says the sniveling creep caught sniffing around her crotch while she pretends to be incapacitated. “Are you?” she quips.

Those scenes reminded me of all the times I thought I was safe with someone, and then realised, in a rush of fear, that I wasn’t. It did what cinema is supposed to do. It captured a moment that I’ve lived through countless times but had never seen on screen. It helped me see myself more clearly.

The reviewers didn’t agree. They thought Cassie’s behaviour was reckless, unfocused, even unfair. One reviewer characterised Cassie’s mission as trying to goad innocent men into bad behaviour. “Not only are men just as bad as you always thought they were, they’re worse.”

Reflexively, the reviewer centres the men and their feelings of being wronged. They don’t understand that Cassie’s battle is as much with the culture that allows sexual violence to continue unabated, as with the individual people who destroyed her friend. Not to mention that she isn’t targeting men, the would-be assailants self-select. The film critiques the self-described good guys, the ones who think “Oh I’d never do hurt a woman” and then come perilously close to doing just that. For these men, being forced to see who you really are is infinitely more unsettling than anything else. It’s probably time for me to say #NotAllMen. That’s what we’re supposed to say, even if it does feel rather infantile. So yes, of course, it’s #NotAllMen but it is an awful lot of them.

Judging Cassie

Reviewers are tasked with judging this film as a cultural product, but it’s striking how often those judgments land on Cassie. They judge her anger, her choices, her appearance, her failure to go to therapy, her “lecturing”, her “risky behaviour”.

I shouldn’t be surprised. Survivors (& to a lesser extent, their supporters) are always judged. People are constantly assessing whether or not we deserve to be believed, if we were somehow at fault, if we seem trustworthy. Rape culture wires people to doubt survivors, to disbelieve their experiences and question their credibility.

Here are a few of the ways that reviewers judge Cassie.

Her rage

One reviewer chastises Cassie for “allowing herself to constantly simmer in rage over injustice”, as if her anger isn’t justified. As if she’s at fault for “allowing herself” to feel her emotions, to be in pain. Rage is an acceptable, understandable response to trauma. It may be temporary, or it may burn for decades. Survivors and the people close to them don’t owe anyone their recovery. We shouldn’t expect them to rise from the ashes like the heroine of a self-help book.

Her “lecturing”

The same critic used the word ‘lecture’ (twice!) to describe Cassie, as if she’s a hectoring academic rather than a grief-stricken young woman. Of course, there’s no such lecture. The horror in this film comes from showing people who they really are, but the language used says a lot about how we see women and their emotions. Another example: this reviewer describes Cassie’s laser focus on her mission as “exhausting”.

Her “risky behaviour”

Reviewers criticise Cassie’s revenge mission as risky. “Though her mission’s important, she’s still going to men’s houses in the middle of the night without informing anyone or guaranteeing she’ll have an escape plan,” wrote one reviewer. So if something happens to her, she’d be at fault? Because she put herself ‘at risk’ by going home with a guy she met in a bar. Risk-taking is often a consequence of severe trauma. Reviewers blame Cassie for it, rather than placing responsibility back where it belongs: with the rapist and his enablers.

Her failure to go to therapy or ask for emotional support for her trauma

This review spends considerable time critiquing how Cassie reacts to the death of her best friend and the end of her life as she knew it. This criticism assumes that Cassie believes she deserves help, that it will be forthcoming if she asks for it and that it will, indeed, be helpful. It fails to understand the depth of her guilt and grief, and the heart-breaking complexity of being alive when someone you love is dead and you feel (rightly or wrongly) that you could have prevented it. It’s easy to say “Go to therapy!” It can be very, very difficult to actually do it. It’s the kind of well-meaning, presumptive comment that places all of the responsibility on her. It expects her to tidy up her emotional mess and not inflict it on others, while saying nothing of the people who caused her this pain. Cassie’s self-isolation could also be understood as a survival mechanism. Rather than continuing to live in a world steeped in rape culture, she leaves the life she knew behind.

There is, of course, very little criticism of how the men in the film behave. There is no commentary on their rage, their “lecturing”, or their need for therapy. Some of this makes sense. Cassie is the film’s protagonist. It makes sense that reviewers focus their attention on her. Though I wonder how many of the same reviewers thought it appropriate to judge the behaviour of the protagonist in Gladiator, another celebrated revenge thriller?

Promising Young Woman vs Gladiator

The 2000 epic was directed by Ridley Scott and won the Oscar for Best Picture. The film chronicles the quest of General Maximus Meridius to avenge the murder of his wife and child. It’s a reference Fennell herself cited, though not a single critic I read did. Is it because Gladiator examines masculinity, while Promising Young Woman leans into a sometimes cartoonish femininity?

For me, the most cathartic thing about Promising Young Woman was the idea that sexual crimes are worthy of revenge. For most survivors, including myself, achieving justice through the legal system is almost impossible. I find the concept of justice for sexual crimes to be a confounding one. What justice can there be for the permanent, irreversible corrupting of your brain and body?

If a child is abused in their earliest years, their brains are permanently rewired. The consequences of that violence live on in their bodies for the rest of their lives. If they grow up to have children, that trauma will be passed to the next generation epigenetically. The average length of a custodial sentence for sexual offenses is 52 months.

For the vast majority of us, there is no investigation, no trial, no verdict. We are left to quietly rebuild our lives knowing that someone could do this and get away with it. This film says that rape doesn’t have to be swallowed and internalised, rotting your life from the inside. It is a crime worthy of vengeance. Cassie makes her plan in a lined copybook, systemically seeking vengeance and showing perpetrators, would-be perpetrators and bystanders the truth of who they are.

I found it cathartic not because I’m going to launch my own crusade against the people who harmed me, but because it was psychically satisfying to watch Cassie fight for what she believes in, just as General Maximus did in Gladiator. I wonder if part of what reviewers failed to understand about this film was the profound closeness that exists between female friends. The bond between young women can be deeper and more impactful than family relationships or romantic love. In a world that often minimises the importance of friendship, perhaps reviewers failed to grasp the potency of the connection between Cassie and Nina.

Regardless of the reason, the contrasting critical reception to these films is telling. No critic ever judged how Maximus went about his vengeance, or the idea that the murder of his wife and child made vengeance justifiable. But you’re not supposed to make a fuss about rape. You’re supposed to seek therapy and stay quiet. Cassie is trying to redress an injustice that was swept aside by not allowing anyone to forget. She is making a fuss and reviewers judge her for it.

Promising Young Woman isn’t considered an epic revenge film like Gladiator. It’s a “commercial girl-power-lite narrative”. Rather than celebrating Cassie’s righteous rage, critics pity her. They comment on her exhaustion, her distrust, but not her steadfast commitment to her task. Not her determination, powered by love, to avenge her best friend’s death.

Reading the reviews, I found a troubling tendency to minimise the horror of what has happened. One review talks about her former classmates who “contributed to the culture of disbelief surrounding Nina’s rape”. Or, to put it more bluntly, the people who watched the rape happen either in real-time or through the recording that was made. This is more than a “culture of disbelief”. That is standing by while someone is raped. This is filming someone being raped. This is circulating a video of someone being raped. This is laughing at rape.

The ending

The film ends with a suicide mission. Cassie sees the recording of Nina’s rape which includes footage of the man she’s been dating laughing at the attack. She dresses in a candy-coloured wig and goes to the rapist’s bachelor party, knowing that she might not come back alive. To me, it’s a profoundly logical choice. Why would you want to live in a world where people laugh and film as a vulnerable woman is assaulted?

Al (the rapist, played by Chris Lowell) suffocates her with a pillow. It takes about two-and-a-half minutes to smother someone. That’s how long the scene is. We see, in slow agonizing detail, Al choosing again and again to end her life. "This is not your fault," his friend says the next morning before they burn her body, kicking a manicured hand into the flames.

Thanks to Cassie’s plan, the police arrive soon afterward and handcuff the groom on his wedding day. I didn’t love the ending and wasn’t surprised to read that the original version included no such retribution. The reviewer for Time magazine criticised the film for “trying too hard to be cathartic”. Others disliked the ending because it lacked hope. Most women, and a significant portion of people of all genders, have experienced sexual violence. Hope is not what we need. Fury is.

Several critics recommended survivors not watch the film. I disagree. There are no scenes of sexual violence in the film and women’s bodies aren’t used to depict the physical embodiment of that trauma. If survivors were interested in watching something on these themes, I think this film is worth watching. We should give survivors the respect of allowing them their own reactions.

Not a perfect film

‘Promising Young Woman’ is not a perfect film. I previously referenced the racial blindspots in the story from the casting of Laverne Cox as an underdeveloped side character to the failure to acknowledge Cassie’s whiteness as a large part of the reason she’s seen as unthreatening and vulnerable.

Another critic (& survivor) notes how the film fails to consider the concept of consent outside of the sexual realm. “This is a film about Cassie’s grieving process, but that comes at the price of a sexual assault survivor being stripped of her personhood,” she writes, which is a valid critique. We never meet Nina who exists in the movie as a shell of victimhood, rather than a whole character.

I enjoyed this film. I’m glad I read the reviews, though I felt a boiling frustration at how they failed to understand either the film or the omnipresence of sexual violence in society. It was less that they didn’t like it, but more that they didn’t get it. Several saw it only as an attack on men, exhibiting an almost deliberate unwillingness to acknowledge the systemic nature of sexual violence. I was troubled by their unquestioned Himpathy, their judgments of Cassie, their failure to grasp the depth and breadth of her pain and how it motivated her.

This film is a reflection of the world as it is. A world that’s set up to protect predatory men, minimise the violence they inflict and disbelieve the women who suffer. It captures something important about rape culture. That it is so ever-present as to be almost invisible. Even when something awful happens, you’ll have to convince people that it is true. You’ll have to overcome generations of conditioning that have shaped our society into minimising violence particularly when it’s perpetrated against girls and women. You’ll struggle not to sink under the weight of everyone else's determination that everything is fine, nothing happened, it’s not a big deal.

Rape is a decimating force. The fact that people are destroyed by it is not that surprising. It’s sexual violence that unspools Cassie’s life, not the revenge she seeks. The catharsis I felt watching her decide that some things aren’t worth surviving stayed with me long after the final credits rolled.

The critical response to this film echoes society’s biases and blind spots. It says something about how we expect survivors to behave, what they are responsible for and by contrast, how little is expected of men. It shows how comfortable we, as a culture, feel about telling a survivor what to do, what their trauma means and how they ought to process it.

None of this matters to the filmmaker who won an Oscar and has a new film coming soon, but it matters to the survivors who live in a world where avenging another woman’s rape makes you deserving of judgment and derision.

The truth is nobody is in any position to judge. We survive however we can, with our teeth clinging to the edge of the world if we need to. What we do with our experiences, how we metabolise them, is entirely up to us.

Bibliography:

In writing this piece, I read several reviews including:

How “Promising Young Woman” Refigures the Rape-Revenge Movie (The New Yorker)

“Promising Young Woman” Gets Lost in Its Own Revenge Plot (Bitch Magazine)

Promising Young Woman’s Flaws Run Deeper Than Its Bad Ending (Slate)

Promising Young Woman Is an Incendiary Revenge Movie With a Sugar-Sweet Shell (Vulture)

On the Disempowerment of Promising Young Woman (Roger Ebert)

Other things I read/watched:

Emerald Fennell’s Dark, Jaded, Funny, Furious Fables of Female Revenge

Let’s Talk About the Knockout Ending of ‘Promising Young Woman’

This conversation on the ending (YouTube)

Thanks for reading! If you’d like to get the next installment in your inbox, please subscribe using the link below. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend.

Hat tip to the film's costume designer, Nancy Steiner.

I've been meaning to watch this. Big fan of Carey Mulligan. Thanks for sharing 🙂