Bad Faith

On Catholicism, trauma and how I left my faith

Welcome to Life after Trauma; I’m Clare Egan. I founded this community in 2023 because I wanted a space for survivor-centred conversations about recovering after sexual violence. It’s grown in leaps and bounds since then, and I’m deeply grateful to be invited into your inbox.

If you look forward to my essays and would like to make this work more sustainable, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your support allows this newsletter to reach more people rebuilding their lives after trauma, and I really appreciate it.

I was a Catholic because I was born to a Catholic family in a Catholic country. The Catholic Church got its tentacles into my body in my first weeks of life. It set out a menu of rituals to cement my commitment to something I couldn’t understand. I was baptised and prayed for.

When I was born, homosexuality was illegal. I was born a crime. A gay child in a homophobic family in a homophobic church. I learned that gay people were “intrinsically disordered.” Like most things, my family’s beliefs were rooted in the church’s beliefs.

Every February, we gathered rushes and wove St Brigid’s crosses. She was a special saint, though the textbook didn’t mention that one of her miracles was performing an abortion.

Every May, I made an altar to Holy Mary. There’s a photo of me standing next to a vase of droopy daffodils. I’m wearing a tan sleeveless jacket over a blue jumper, as an image of Jesus looms ominously over my shoulder. Looking at the photo now, I see only sadness in my big, blue eyes.

I learned to recite my prayers fluidly; prayers that will probably live in my muscle memory until the day I die.

At 6, I made my first confession but was too shy to confess anything. If I’d been brave enough to speak, I probably would have apologised for fighting with my siblings. A younger sister and brother had arrived a few years before. I resented how they’d commandeered the attention my mother used to shower on me.

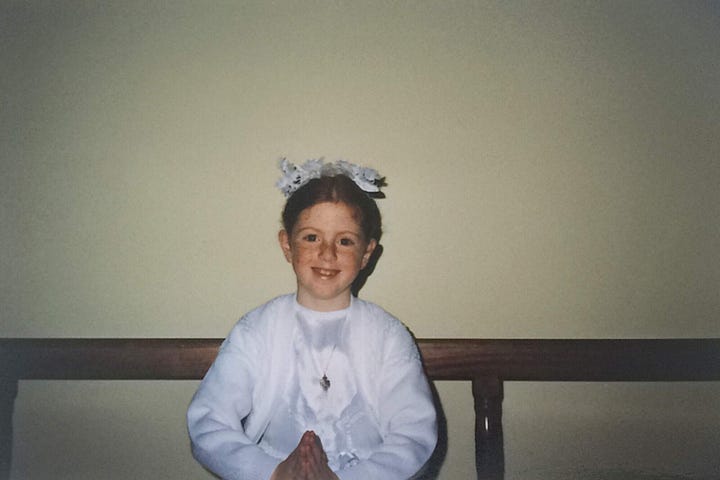

At 7, I made my communion in a virginal white dress. The dress was a lie.

My mother was very religious; she was part of a prayer group, and she organised the church choir. She directed the nativity play, complete with tea towels on small children’s heads to approximate the Shepherds. She was friends with the priests and washed their vestments in our kitchen. We went to mass as a family every Sunday but she went more, slipping into the church after dropping us at school. When she had problems in life, she went to talk to a priest about them. Her faith was the organising structure for her life and the backdrop to my childhood trauma.

During these years, unknown to most of the “ordinary faithful,” people who’d been raped and sexually assaulted by priests began reporting these crimes to the Gardaí. As I entered adulthood, four reports detailing the systemic sexual and physical abuse of thousands of children in Ireland were published. The investigations focused on particular dioceses (Ferns, Dublin and Cloyne) together with the Ryan report, which examined the systemic abuse of children in residential institutions operated by the Catholic Church but funded and supervised by the Department of Education. Collectively, the reports found that rape was “endemic” and that the church protected pedophiles from prosecution. They detail how the church knew the recidivist nature of sexual crimes and that they routinely facilitated rather than prevented the abuse of children.

Read that again: the Catholic Church facilitated rather than prevented the abuse of children.

Despite overwhelming evidence contained in the reports, only a handful of perpetrators were prosecuted for their crimes. Almost 15,000 survivors came forward as part of the Ryan Report but Ireland’s Director of Public Prosecutions agreed to prosecute only a few cases. The church agreed to pay damages but, fifteen years later, more than 80% of that money has yet to be paid. The last church-run institution closed in 1996. The past is close.

Throughout my childhood, there was a slow drip of stories framed by the media not as crimes but as scandals. Even today, Google autocompletes the phrase: “clerical sex abuse scandal” which I just searched and discovered another story reported in the last few months about a priest who lived a few kilometers from my childhood home. Media reports about the “scandals” were framed as “the fall of an institution,” though that institution still runs 96% of schools and owns land, wealth and property in every part of Ireland. The Catholic Church has a reach matched only by the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA)1.

These media stories focused on the abuse committed by “the religious”- a clunky term meant to include priests, brothers, nuns and others affiliated with the church, working in church-run schools and institutions. The term pedophiles is more accurate. Why would we identify perpetrators by their jobs rather than their crimes? Is it because that allows the Catholic Church to remain a religious institution and not an international criminal organisation? Is it because research has shown that the prevalence of sexual abuse among priests is sufficient to be a recognisable psychiatric phenomenon?

Psychiatrist and former priest Richard Sipe estimates that “2% of all Catholic priests are sexually involved with prepubescent children (pedophiles) and 4% of Catholic priests are sexually involved with adolescents (ephebophiles).” According to the Vatican, there are 407,872 priests in the world. Studies have shown that the average pedophile has 250 or more victims over his lifetime. I’ll let you do the maths.

Pedophiles create opportunities to prey on children, and they gravitate towards professions where they have access to children. The Catholic Church has proven, time and time again, that it’s a safe space for pedophiles to perpetrate their crimes.

The Catholic Church is only a front for an international pedophile ring.

As you can imagine, the impact of child sexual abuse is severe and long-lasting. Survivors of sexual abuse are three times more likely to develop psychological disorders in adulthood. Depression, anxiety, eating disorders, substance abuse, suicide attempts and PTSD are common. Survivors are also more likely to experience physical health problems including diabetes, gastrointestinal problems, gynaecological problems, stroke and heart disease. One US study put the average lifetime cost per victim of child abuse at $210,012. The harm doesn’t stop with them, but ripples out into their families and communities. Survivors can also pass their trauma to the next generation epigenetically.

If it seems like I know a lot about this, it’s because I do. I was sexually abused, not by a cleric but by an adult within my church’s community that everybody liked and trusted. I have spent my life trying to recover. I could list my symptoms, perform my pain for you. I could detail every nightmare, every memory, every sleepless night, every broken relationship. I could enumerate all the “normal” parts of life that aren’t available to me anymore. But I won’t do that. I won’t do that because countless others have and little has changed.

When my mother died, I reached for her Catholicism. She was gone, but nurturing the faith that had sustained her felt like a way that we could remain connected. I remember wandering into the eerie church close to my college campus, sitting in a pew and trying to contain my sobs. The church felt like an anchor to her, a solid piece of ground where I could put my foot in a newly weightless world.

I was breaking all the rules, of course. Living a sinful life by having sex and being prideful, ambitious and feminist. I voted for marriage equality and campaigned for abortion. I thought of myself as a spiritual mongrel. Someone who no longer believed in the church’s teachings, but who maintained a sense of reverence for ritual and contemplation. A nostalgic attachment to a set of beliefs that had given my mother’s life meaning. But even that was more than I could bear.

As a teenager, I had recoiled at how women were only welcome at the altar when they were assisting men. My feminist consciousness was just beginning to take shape, and I couldn’t abide this blatant discrimination. Every Sunday at mass, I’d watch a woman get up from her seat in the congregation and bring a chalice to the priest so that he could do the magic bit. The “magic” is transubstantiation. The belief that the bread and wine are transformed into the body and blood of Christ, not metaphorically, but literally. “But that’s cannibalism,” my younger brother said, incredulous. He didn’t mean to be funny, but everyone laughed.

Today, being in churches (as I sometimes am for weddings or funerals) always makes me think of what has happened in these rooms. We know that children were abused in these rooms, surrounded by the smell of incense, where people speak in hushed tones out of respect for God. We know that children were raped with crucifixes. I can’t bow my head to one knowing that.

For a while, I tried to make a distinction between the institutional church and my personal experience of faith. But that didn’t work. It’s all the institution. You can’t separate the belief that gay people are “intrinsically disordered” from the belief that God loves everyone equally. And I can’t show reverence to an institution responsible for the systematic abuse of children over generations. Abuse which all but certainly continues across some of the Catholic Church’s 3,500 dioceses across the world. Across parts of Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, South and Central America, the church’s dominance remains strong. Who protects those children?

Trying to maintain my Catholic faith, both for myself and for the connection it gave me to my late mother, required a level of disassociation that was unhealthy for me to maintain. Disassociation is a symptom of PTSD. It is a mark on my psyche caused by what I have survived. When my childhood body was violated, my mind separated from it because the horror was simply too severe to withstand. Decades later, disassociation still lives in my cells. On hard days, I watch my life happen from a ghostly distance hovering in the top right corner of the room. Sitting in a chair, I look down at my legs and fail to recognise them. They don’t feel like mine. They don’t belong to me. I spent years like this, existing in a dissociative haze, trying to keep myself alive.

I used to believe that God was always watching over me. I was taught that He would take care of me whenever I was sad or worried. I wonder how my young self could have accommodated that belief with the reality of sexual abuse. Was God, like everyone else, prepared to look the other way?

A few years ago, the Catholic Primary Schools Management Association published a new curriculum to educate children about relationships and sexuality. A lesson on safety and protection “advises senior infant children to say the ‘Angel of God’ prayer” when they feel scared. “Puberty is a gift from God. We are perfectly designed by God to procreate with him” is part of a lesson for senior classes.

Reading that, I almost stop breathing. As an adult, I have spent years trying to evacuate the abuser’s words from my body. It is bone-chilling to see the Catholic Church’s curriculum echo the language used by priests grooming and sexually abusing children. Phil Saviano, a survivor of sexual abuse in the Boston diocese, recounts part of his experience in the 2015 film Spotlight:

"When you're a poor kid from a poor family, religion counts for a lot. And when the priest pays attention to you, it's a big deal. He asks you to collect the hymnals or take out the trash, you feel special. It's like God asking for help. And maybe it's a little weird when he tells you a dirty joke but now you got a secret together so you go along. Then he shows you a porno mag, and you go along. And you go along and you go along, until one day he asks you to jerk him off or give him a blow job. And so you go along with that too. Because you feel trapped. Because he has groomed you. How do you say no to God, right?”

Reading that, I dissociate. I close the document. I try to leave it aside. I do what I often have to do living in Ireland. I try to stretch my psyche to contain these duelling realities, to accommodate an incredible amount of cognitive dissonance. That thousands of children were targeted and abused by people in the Catholic Church, and that 96% of primary schools in Ireland are still controlled by the Catholic Church. That in 1979, Pope John Paul II came to the Phoenix Park and proclaimed his love for the young people of Ireland while at the same time, priests were raping children. That Tommy Tiernan can spend 20 minutes on the radio giving out about the crushing yoke of Catholic oppression before signing off with a sincere “God Bless.” That children, gay and straight, cis and trans, are taught to be ‘Christ-like’ in their decision making, to be aware of “moral as well as physical dangers.”

When I look back on the church of my childhood, I see only trauma. I wish I could say that once I realised the harm the Catholic Church had caused me and countless others, I cleanly left it aside. But that isn’t true. I yearn for the still, steady faith I know others have found. I would love to be part of a church, though I have also spent much of my life trying to recover from it.

I’ve worked hard to unravel the church’s teachings from my psyche - that homosexuality is wrong, that we must always forgive, that God is always watching. I catch myself preparing for the day of judgement, rehearsing my speech for when I stand before God and have to account for myself. I try to dispel the idea that humanity is neatly divided into “good” and “bad” people. “You do not have to be good,” writes Mary Oliver. I paste her words to my wall, hoping they’ll bleed into my psyche. But perhaps it’s not so simple. I am no longer a Catholic, but I rely on grounding spiritual practices to soothe the worst of my c-PTSD. Large chunks of my recovery have happened on my yoga mat, in meditation, with my journal and in conversations about the things we can’t see but deeply understand. While my mother’s devotion was to God and her church, mine is to the power of recovery, community and what we, as humans, can survive. From this vantage point, those things feel startlingly similar.

💕 If this piece resonated with you, please tap the heart below to help spread the word.

💬 In the comments, I’d love to hear about how trauma has impacted your faith. Religious trauma is incredibly common, though there aren’t many places to talk about it. If you’re open to it, I’d love to hear a little of your story in the comments below.

The Gaelic Athletic Association is an Irish sporting and cultural organisation, which promotes our national games. It has a presence in every village in Ireland, and hundreds of clubs around the world.

Thanks for this courageous share Clare, very moving and powerful ❤️

I also used to believe God was watching over me. Maybe I was told one too many times that "God never gives you more than you can handle." Or that "this is a test." Something broke a long time ago. Or maybe not broke. Dissolved? The point it, so this speaks to me. Thank you for writing it.